Changing the way we talk about design

It’s sometimes easy to assume that our designs will just speak for themselves.

We’ve all been in that design review where you’re really proud of your work and confident that everyone will agree your solution is the best possible one to go forward with. But this time, that doesn’t happen - instead, people question your design decisions and the discussion begins to go off on a tangent that ends up miles away from the designs in front of you. You’re confused and frustrated, why can’t people just trust your design expertise? Instead of blaming the people who gave you bad feedback, perhaps reflect on how well you delivered your work.

Talking to people about your designs is a basic skill, but one that is generally overlooked and can be difficult to do well. I read the book ‘Articulating Design Decisions’ by Tom Greever, and learnt that a lot of designers often struggle to communicate their ideas effectively. Failing to do this well not only causes unproductive meetings, but could also lead to implementing design solutions which might not be in the best interest of the user and impact the success of the project.

So how can we get better at articulating our design decisions? Much like we would do at the beginning of the design process, we first need to define who our audience is and understand what they need. Only then we can begin to improve the way we communicate with them.

1. Who are we talking to?

Everyone is a designer!

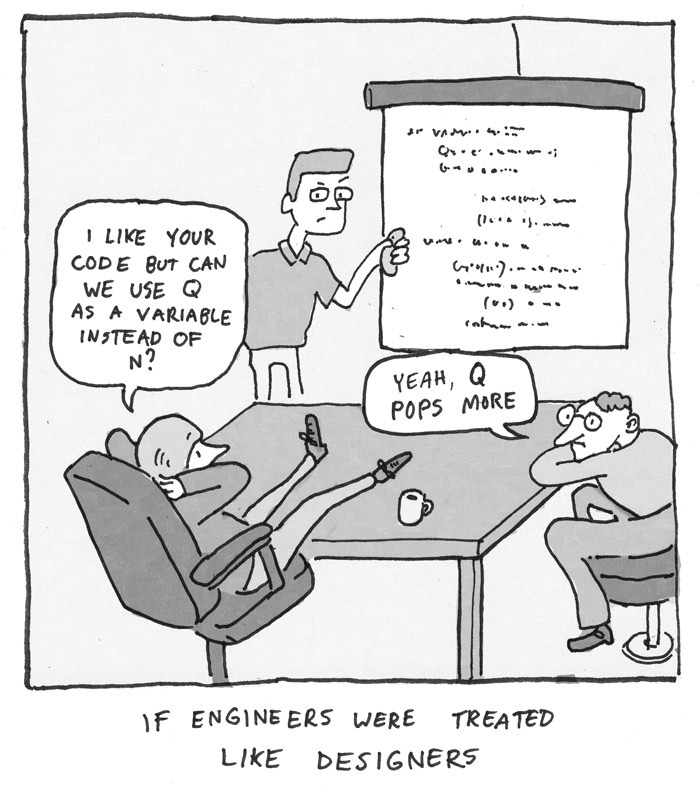

Quite often, the people we are talking to in meetings about our designs, aren’t experts in design themselves. Yet, they still request changes that go directly against your professional opinion. This isn’t necessarily because they think could do a better job than you. The reason people feel so comfortable expressing their opinions of your work is mostly due to the nature of design being so visual. While this can be a frustrating realisation for designers, the truth is that everyone does this for most art forms. For example, I may not be able to sing in key, but I certainly know what music I do and don’t like listening to!

Andy Zelman, Skeleton Claw Comics

It’s easy for someone to say that they don’t like something, but it’s more difficult for them to explain why and articulate what specifically about it doesn’t work. That’s why in his book, Greever encourages designers to convert people’s “likes” into “works”. For example, if someone says that they don’t like where you’ve put the call to action on a screen, you could respond with: ‘I understand that you want us to move that call to action over there, but why doesn’t it work to have it over here?’. This might make people realise that their feedback is derived from a personal preference, rather than something that would benefit the user experience. Or it might just help that person articulate their point more clearly, which in turn will help you to understand their thought process - it works both ways!

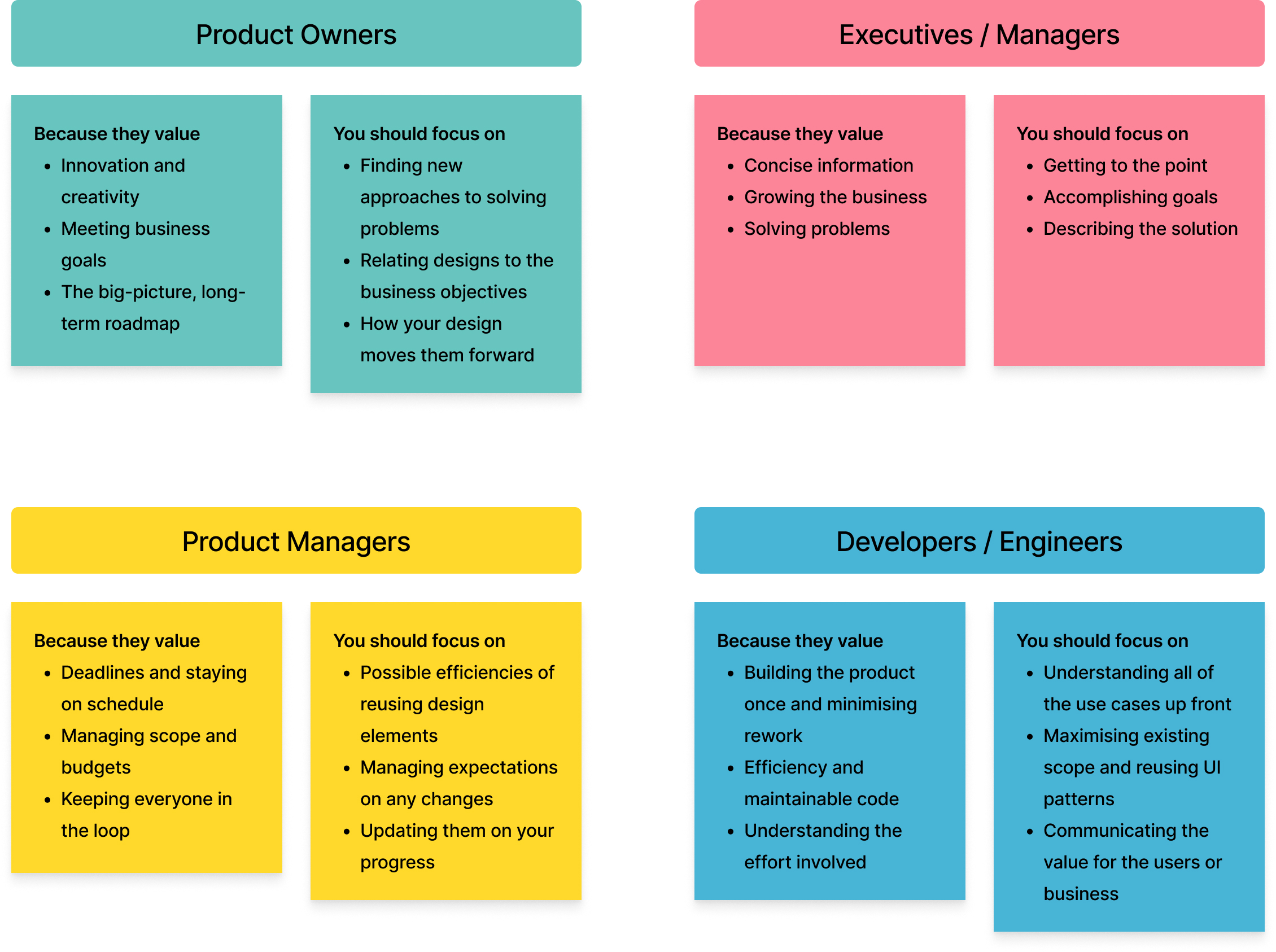

Understanding what people value

It’s important to remember that everyone has different experiences which can influence their thoughts and reactions to your designs. That’s why it’s good to build relationships with stakeholders, so you can learn more about them and their way of thinking. It’s also beneficial to know each stakeholder’s role in the business in order to understand how this will affect their perspective of your work. In his book, Greever breaks down some of the different types of stakeholder roles and notes how you could align with their position.

So while you don’t have control over the subjective nature of design, we can control the way we talk to people about our designs. And if can present our work in such a way that appeals to stakeholders’ needs and expectations, we can help them see that our designs provide the best possible solution.

2. How do we talk to them?

Question your own thinking

People often struggle to articulate themselves when talking about their designs if they haven’t previously questioned their design decisions. Greever implores designers to constantly reflect on their own thinking whilst working on designs, questioning:

- What problem does this solve?

- How does it affect the user?

- Why is it better than the alternatives?

Writing your answers to these questions down might help you to remember them later on in meetings. Be it using post-it notes, lists, grids, free-form writing or just annotating your designs, the format doesn’t hugely matter. What’s important is to note down the problem and the solutions that you are proposing.

You could go a step further with this activity and try to anticipate what people might respond with, ask or suggest that you implement. Bonus points if you think about (and note down) how you might respond to that. For example - you might think that people will ask why you didn’t go with the most obvious solution to the problem, so you prepare the reasoning behind your design decisions. You could even show an early version of the designs, where you did try out that “obvious solution”, to provide them with a visual aid whilst you explain to them why it didn’t work.

Design a better meeting

In his book, Greever argues that we should put more importance on how we deliver our designs in meetings. We often spend time and effort curating a flow for our users through the product, but we don't tend to put the same thought into creating a “flow” in design discussions.

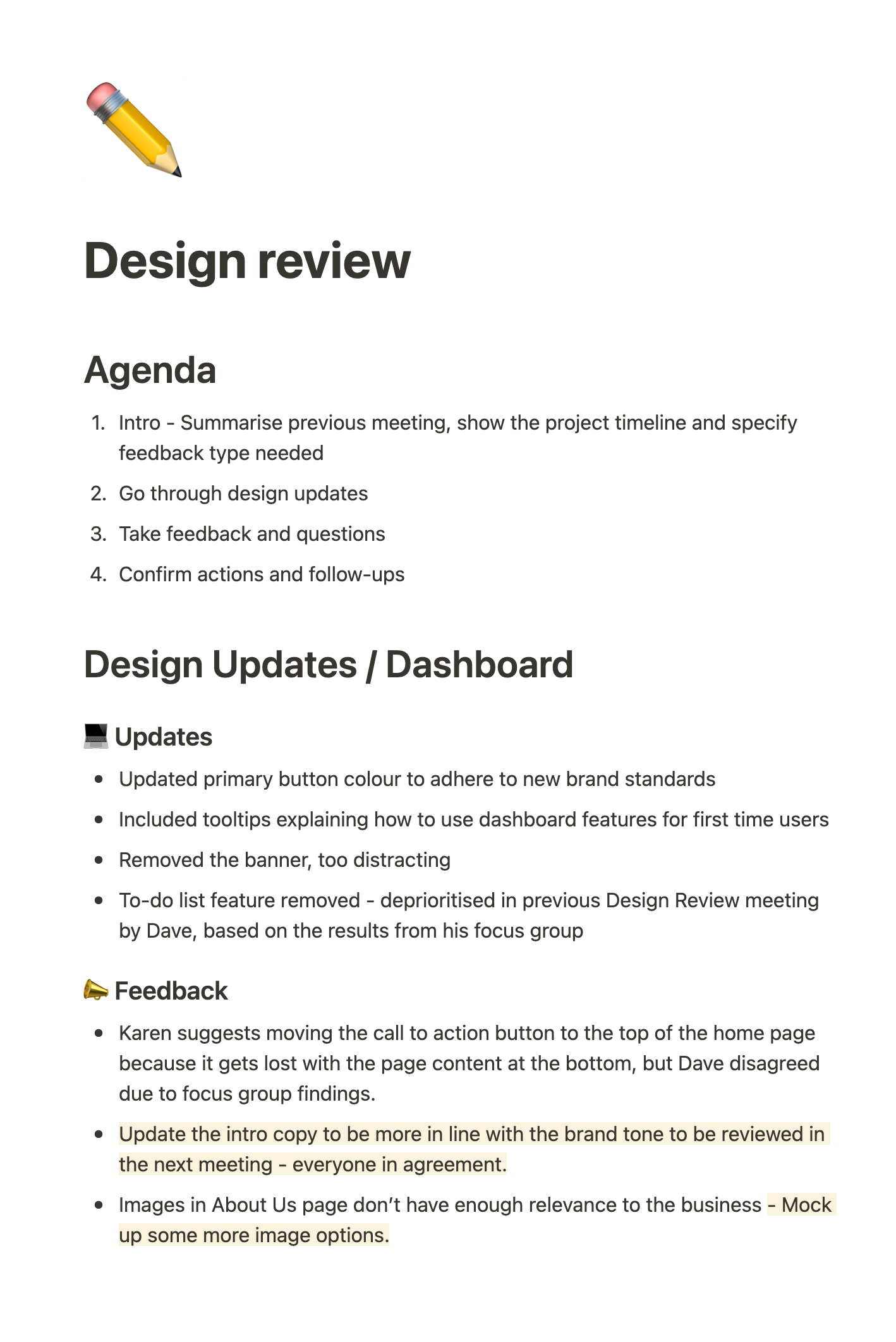

This probably won’t be a surprise to anyone, but the key to designing a better meeting is preparation. We generally only have a short amount of time to present our designs during these sessions and it might seem like an impossible task to fit everything in. However, there are a few simple things that we can do before the meeting has even begun, to increase the effectiveness of that session. At Inktrap, we find it beneficial to give the meeting a title, such as ‘Design Review’ or ‘UX Research Insights’, and write a high-level description of what the meeting is going to be about. Sharing this with the attendees in advance helps everyone be on the same page about what the meeting is for, and consequently makes our time with stakeholders more productive.

During the meeting itself, make sure to clearly state the goal for the project or piece of design work that you are presenting. You can start by summarising the last meeting to set the context and remind everyone of the decisions you made together. It can also be helpful to show a timeline to help people visualise where you are in the process of your design.

As previously mentioned, it’s crucial to have reflected on your design decisions beforehand in order to clearly articulate them. We can prepare ourselves for meetings by practising our presentation and thinking through potential responses. However, we still might get unsolicited feedback and suggestions from our audience if we aren’t clear about the type of feedback we are looking to receive from that particular session. For example, if it’s a review of the UX Wireframes, specify that you’re looking for feedback on the layout and hierarchy of elements on the page - rather than anything to do with styling.

Finally, make sure to document the meeting thoroughly. Taking detailed notes during these sessions is not only helpful when it comes to prepping for your next one, but they can also be used as reference points in future meetings. When recording feedback, make sure you detail the suggestions as best as you can, including who said what and why - highlighting any decisions that are made. At Inktrap, we try to keep our notes really organised by clearly labelling the different sections i.e Agenda, Design Updates, and Questions. We’ve also found that it can be helpful to structure the notes you take during the design discussion by different screens or features.

It’s also important to include a specific ‘actions’ section at the end that clearly lists all the design updates you need to do. You could even add a ‘follow up’ section underneath that, which lists all the things you need to follow up on.

To conclude…

I think the key takeaway from ‘Articulating Design Decisions’, is that we need to give more importance to the way in which we talk about and deliver our designs. We need to create our own processes around preparing for meetings and think about how we are going to articulate our design decisions in them. But we also need to treat this case by case, because a lot of it is down to our audience - which often changes over the course of different projects. Getting to know the people you are presenting to, listening to their perspectives and understanding how their role will influence their feedback on your designs is an important practice. The purpose of all of this isn’t to try and manipulate people into agreeing with you, it’s to help us become more aware of the decisions that we’re making during the design process which in turn, will improve the way we explain our designs to other people.

Get in touch

At Inktrap, we design great digital products. For 10 years we’ve been helping technology businesses focus on their users, from early-stage to funding and beyond. Talk with us to discuss your current challenges, we'd love to help.

Let's get started

Chat with James

Book a free discovery call with our co-founder to see if we’re a good match for your requirements.